Musical Mirror

philosophical and poetic thoughts on music

Isao Tomita

Electronic and classical music combined

At the turn of the 20th century, when Claude Debussy sat down to write his haunting piano piece “Clair de Lune,” he had before him little more than pen, paper and piano.

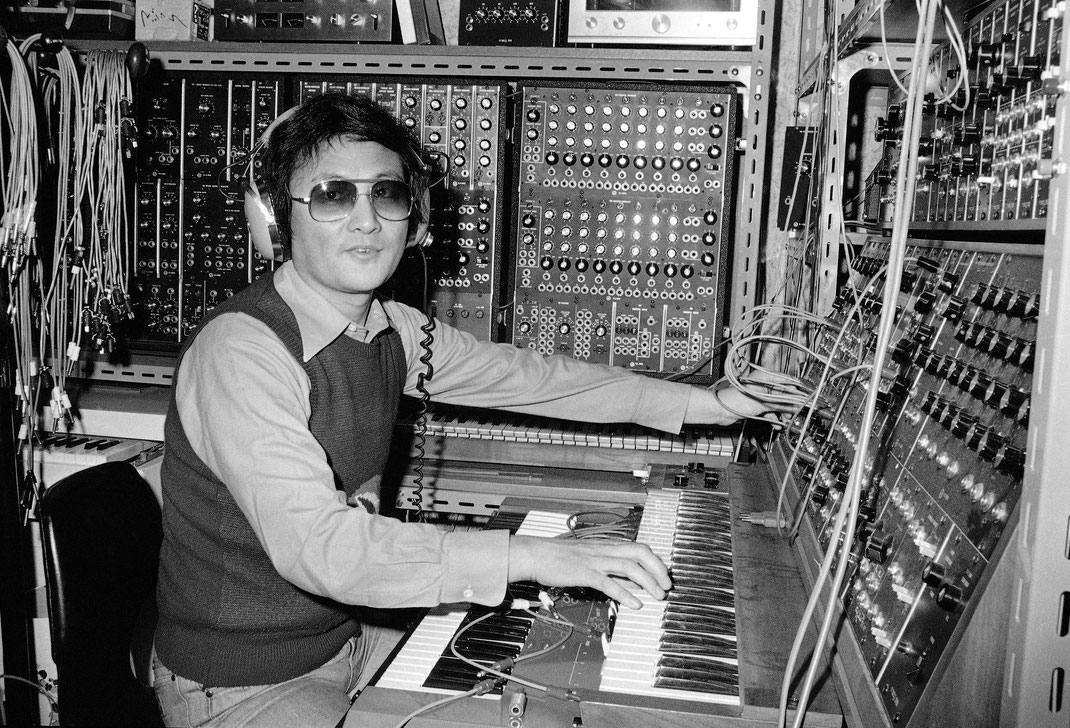

Toward the end of the century, when Isao Tomita sat down to record the piece, he had before him a thicket that included a Moog synthesizer, comprising (among many other things) a 914 extended range fixed filter bank, two 904-A voltage-controlled low-pass filters, nine 901-B oscillators, four 911 envelope generators, five 902 voltage-controlled amplifiers, a 950 keyboard controller and a 6401 Bode ring modulator; several tape recorders, among them an Ampex MM-1100 16-track and a Sony TC-9040 4-track; two Sony MX-16 mixers; an AKG BX20E Echo unit; an Eventide Clockworks Instant Phaser; two Binson Echorec 2 units; and the electronic keyboard instrument known as a Mellotron.

Released by RCA in 1974, the resulting recording, “Snowflakes Are Dancing,” brought Mr. Tomita — who died on May 5, at 84, and was widely considered the father of Japanese electronic music — international renown. Nominated for a Grammy Award for best classical album, the record, containing Mr. Tomita’s renditions of a string of Debussy pieces, sold hundreds of thousands of copies, an almost unheard-of feat for a disc at least nominally rooted in the classical world.

It also divided that world, much as the album that inspired it, “Switched-On Bach,” by Walter (now Wendy) Carlos, had done on its release in 1968.

Some critics commended Mr. Tomita for the “exhilarating glee” of his music, as The San Francisco Chronicle wrote in 2000, reviewing a rerelease of “Snowflakes Are Dancing.”

Others huffed and puffed. In 1975, discussing the release that year of Mr. Tomita’s rendition of Mussorgsky’s most famous work, Jack Hiemenz wrote in The New York Times:

“Tomita’s electronic transformation of ‘Pictures at an Exhibition,’ like the job he did on Debussy, will disappoint the more musically minded, though it will just as certainly titillate the quad nuts. It’s another four-ring circus, announcing its intent at the outset by having each note of the striding ‘Promenade’ theme issue coyly from a different speaker — a kind of four-point ‘instant antiphony’ that may well give a listener vertigo.”

Undaunted by reviews, Mr. Tomita continued his work, which was reported to have influenced musicians around the world, among them Stevie Wonder and the Japanese techno-pop group Yellow Magic Orchestra.

His success was all the more noteworthy in that he had had to come to terms on his own with the inscrutable behemoth that was his chosen instrument.

Isao Tomita was born in Tokyo on April 22, 1932. He spent part of his childhood in China, where his father, Kiyoshi, was a physician at a textile mill; the family returned to Japan in 1939.

After World War II ended, the young Mr. Tomita became enraptured by Western classical music, along with jazz and pop, through radio broadcasts by the United States Army of occupation.

“I thought I was listening to music from outer space,” he told the English-language Japanese magazine Tokyo Weekender in 2013. “When I was a child, Japan was closed to Western music.”

As a student at Keio University in Tokyo, where he studied literature, he took private lessons in piano, music theory and Western compositional technique.

He began his career as a composer for Japanese films and television; his credits include the television cartoon known in English as “Kimba the White Lion.”

In the late 1960s, he encountered “Switched-On Bach.” Where that album offered a note-for-note recreation of Bach’s music on a Moog synthesizer, Mr. Tomita was determined to use the instrument to augment classical pieces far beyond the composer’s original intent.

“For the first 20 years of my career, I was looking for some new instrument — there have been no new instruments since Wagner,” Mr. Tomita told The Los Angeles Times in 1999. “Then I discovered the synthesizer, and with that I could create by myself the sounds I wanted to have.”

He scoured the world for one — he could find none in Japan — and in the early 1970s imported a Moog from the United States. Then his troubles began.

“At Customs, they asked me what this machine was,” he recalled in an interview with the online music magazine Resident Advisor. “I told them that it was an instrument, and they didn’t believe me. They said, ‘Then, play it.’” Mr. Tomita continued:

“I wish it was that easy, but it takes a while to even generate something that’s not just noise, so I couldn’t play it in front of them. I pulled out an LP of ‘Switched-On Bach,’ which has a Moog on the cover, and they still didn’t buy it. Eventually I had to ask Moog to send over a photo that shows somebody using a Moog synthesizer onstage.”

Then there was the daunting nature of the machine itself.

“It was hell,” he said in the same interview. “I felt like I just paid loads of money for a big chunk of metal. If I can’t make proper sounds, it’s just junk!

“Also, since Moog was a new kind of instrument, I didn’t have a clue how it was supposed to sound because there wasn’t anything to compare it to. So I started emulating existing sounds, such as a bell or a whistle, and went from there.”

Mr. Tomita’s other recordings include electronic interpretations of Stravinsky’s “Firebird” Suite and Holst’s “The Planets,” both released in 1976, and of Ravel’s “Bolero,” released in 1980.

In later years, he staged live multimedia performances that he called “sound clouds” in cities including New York and Sydney, Australia.

from https://www.nytimes.com/